by Michael McCabe

I recently read an articulate essay on the Mises website from 2002 titled “What’s Wrong with Distributism,” by Thomas Woods. In it, he critiques Distributism as being unrealistic and incapable of fulfilling its own criteria. As a distributist myself, I would like to reply to his arguments. Based on his own understanding of the theory, his counterarguments are excellent; I disagree with him because he, along with most other commentators on this website, does not understand it sufficiently.

The easiest way to describe distributism is to call it “Credit-Union Economics.” In this analogy, capitalism functions like a bank:1 in its purest form it is owned by one man, and to him the profits go. All those who work for him do not share in the profits, but work for a wage, and his customers see him and his workers as a means to an end. Distributism, on the other hand, functions like a credit union: in order to work there or use its services one must be a co-owner. Co-ownership is the decisive point of divergence between the two systems, and therefore the hardest to recognize.

At this point some readers will point out that in the real world not all of the profits go to one man, and that shareholders share in said bank’s profits. This does not disprove the analogy, however, as we do not have 100% pure capitalism today. Most of these shareholders are not employees of the bank, so they share in profits that they had little or no part in creating. This, in turn, permits reckless and callous actions by the owners and management. It is, after all, much easier to order a subordinate to work harder than it is to work harder oneself (as the saying goes, if it was so easy everyone would do it). Same with spending someone else’s money, especially if it’s paper/digital and not pure gold.

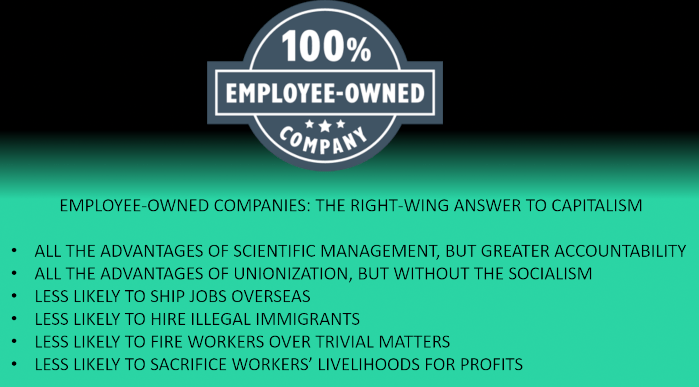

While banks have been reckless through means of fiat currency and hoarding gold, other capitalist industries have practiced the same recklessness and dehumanization through means such as lockouts, importing cheap labor from the 3rd World, and/or outsourcing jobs overseas, often to adversarial and predatory nations such as China. Unionization was created as a response to the terrible conditions of early industrialism, but did not change the propertyless helplessness of the workers. They demanded higher incomes, but remained separate from the profits they helped generate. Noticeably absent from the list of companies which throw their workers under the bus for sub-percentile profits are those which are employee-owned.

This is where Mr. Woods makes his first mistake. He writes that “…it is by no means obvious that it is always preferable for a man to operate his own business rather than to work for another. It may well be that a man is better able to care for his family precisely if he does not own his own business or work the backbreaking schedule of running his own farm, partially because he is not ruined if the enterprise for which he works should have to close, and partially because he doubtless enjoys more leisure time that he can spend with his family than if he had the cares and responsibilities of his own business.” He assumes, not irrationally but still incorrectly, that distributism advocates for every man to own a separate business, and does not permit group efforts. Distributism is not antagonistic, however, to team efforts. Rather, it is centered around breaking Trusts and other anti-monopolistic policies. It relies upon the Catholic principle of Subsidiarity, which in this context argues that it is best to keep individual businesses’ size to a minimum. In layman’s terms, if it requires a minimum of 15 men to efficiently run business X, then it is superior to have 3 business ‘X’s this size than a single business ‘X’ with 45 men. Same if the minimum for business Y is 15,000 or 150,000 for business Z. Subsidiarity maximizes competition and reduces the number of workers who will be affected if one of the businesses fails. Distributism further argues that these three smaller businesses de facto increase private property, and that they ought to be employee-owned whether they are publicly traded or not. By keeping manpower to a minimum, both theories treat work as a human endeavor, rather than treating humans as machine parts.

This ties into the second significant mistake of Mr. Woods, when he argues that distributism would not have granted the benefits of the industrial revolution. This error is more historical than economical, but the two are tightly related. The Industrial Revolution was not caused by a failure of distributism, but by its deliberate destruction by the aristocracy during the Reformation. Prior to the Reformation, the average Medieval peasant was not living in squalor, but was legally protected from being expelled from his ancestral farmland. Serfdom sounds awful to modern ears, but it was not unheard of for a medieval family to voluntarily become serfs to guarantee they would not lose their private property. Guilds, too, functioned more like a credit union of equals/competitors than a competition-crushing monopoly. Besides communal property which was available to all members of the village, the Roman Catholic Church also represented a double-digit percentage of Europe’s GDP, primarily in its monasteries. If a man or family was in a rough patch, they could find aid in the Church for free (those who abused this system were severely punished). Medieval workers worked in safer and more sanitary conditions than those of the early factories, and invented numerous labor-saving devices; today’s robots replacing hand labor in repetitive tasks would not be a radical, new idea to them.2

When the Reformation happened, there was a massive confiscation of wealth by the aristocracy and merchant classes. Farmers were told to present written documentation for the lands they worked and since most of them had never needed such documentation before, the aristocracy could now seize their lands without legal consequences. The monasteries, too, were shuttered by secular authorities before their vast wealth was confiscated. Thus, in a generation, the majority of Europeans went from property-owning serfs, peddlers, & yeomanry to propertyless proletarians.3

Mr. Woods and many readers would at this point argue that if it was so bad, then there would be pushback by the masses being deprived of their property and economic freedom. There was, and it was severely suppressed by the state’s professional armies. Between the state’s bayonets, the loss of private property, and the threat of starvation, it would be silly to suggest the newly-minted proletarians wanted to work in the factories as disposable labor to “improve their standard of living.” The choice between working in bad conditions or starving is not truly a free choice- true freedom of choice is the power to say “no” and walk away from the negotiating table unharmed. Furthermore, Protestantism brought with it a legalistic and merchant-class mentality that spread outside of the merchant class. Christopher Dawson’s excellent essay on the bourgeois mind explains this in greater detail, but it will suffice here to say that the cultural impact of the merchant-class culture permeating all levels of society is why the populace eventually accepted the atrocious working conditions of the factories and slums: it became a point of pride to define oneself by one’s work, rather than by religiosity.

The story would not be complete, however, without mentioning the American clash between plantations and homesteading. In the years leading up to the civil war, there was a spirited debate over whether to seed the west with one or the other. Plantations, whether utilizing slave or sharecropper labor, functioned no differently from northern factories. Yet this system was nowhere near as successful as the Homestead Acts, which allowed the Midwest to surpass the Old South by leaps and bounds. Farmers who owned the land they worked, and peddlers who owned everything they carried, built America while the Old South’s plantation system (and wider culture) stagnated. This, along with the Land Acts which increased private ownership of farmland in Ireland, were used by the distributist movement in the 1910s-1920s to bolster their arguments in favor of returning to the medieval system.

Lastly, capitalism cannot take credit for improving standards of living or reduced working hours. The aforementioned slums and filthy cities lasted well into the 20th Century, and it was Christian culture and morals which demanded they change. Military manuals in the 1920s warned that recruits from agricultural regions were at greater risk of disease since city boys had grown up surrounded by a greater quantity of illnesses. Penicillin was discovered by accident, and the scientific curiosity necessary to make such discoveries is a cultural, not economic, factor. Most of the modern world’s technology/systems to prevent disease/educate youth/improve standards of living exist only because capitalism created the hellish conditions necessitating them in the first place. As for reducing toil, the 80-hour workweek of the industrial era is unparalleled in history. Moderns easily assume that pre-industrial cultures worked longer hours, but this is not backed up by archival evidence. Medieval peasants, for example, enjoyed anywhere between 3-5 months’ worth of holidays (depending on locale) and often worked less than 40 hours per week. A modern-day worker can accomplish in 25 hours what a worker in 1950 required 40 to accomplish thanks to Information Technology, yet moderns have kept the 40-hour week because they are practically married to their jobs like draft animals.

Thus, calling for a return to distributism would not necessitate throwing away the real technological or social progress of the past 6 centuries. It would not entail government planning or price controls, and would counteract the tendency for modern capitalism to drift towards socialism. By abandoning the bank for the credit union, and the globalist corporation for the employee-owned company, we can retain scientific management and replace the hand laborer with the robot to perform repetitive tasks. Distributism aims not to make men into islands, but to give him back control over his own life through economic freedom, rather than being swallowed up by a mass civilization in which he is only a number. This is what most critics of distributism, both economical and cultural, fail to understand. Distributists see Private Property as the “M” in Einstein’s theory of relativity, and money/currency as the “E;” a small amount of property is worth much money. Now imagine increasing both workers’ private property and letting workers share in the profits they helped to generate!

Understanding distributism through the lens of a credit union also makes it feasible to transition without an economic collapse: if employees purchase stocks in the companies that they work for, en masse, then the company would become employee-owned. If renters of apartments did the same for the company from whom they rented, the effect would be the same. Same for farmers, miners, lumberjacks, and every other conceivable industry. Such a move would require a cultural shift, rather than government action (politics is always downstream of culture), but would begin the creation of a genuinely distributist society.

Notes:

1: If I were to apply this logic to communism, I would call it “DMV Economics” which is both amusing and accurate. To my non-American audience, the Department of Motor Vehicles is a government department that cannot perform even the most basic tasks without long lines, delays, and subpar customer service. It’s the closest one can come to experiencing the farce of government planning and management in our nation.

2: Most medieval inventions were limited by energy sources, not lack of resources or imagination. Leonardo Da Vinci could design a functional helicopter, but without an internal combustion engine he wouldn’t be able to power it.

3: I define proletarian here as someone without private property, a renter who relies wholly upon a wage.

I am one of the authors of a new book, Future Visions, that will be available soon. In my chapter I advocate Distributism for a near future event, called the Economic Singularity, in which AI & robotics replace human labor, due to its cost effectiveness. I’d like to discuss this on your podcast. michael.b.diverde@gmail.com

Thanks!